Universe 25

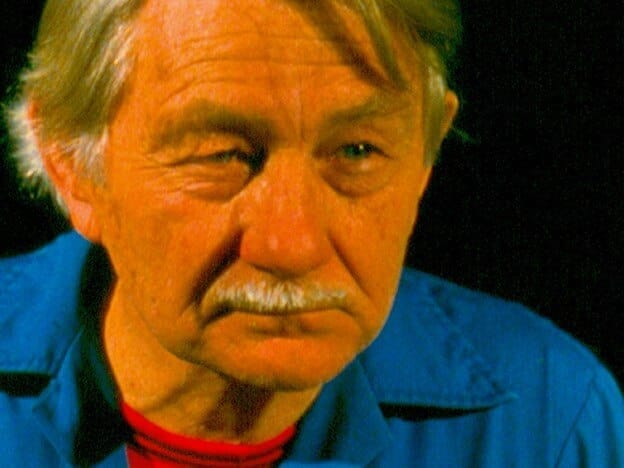

John B. Calhoun [1917 – 1995] was an American ethnologist and behavioral researcher. As a youth, he was a bird enthusiast, spending his teenage years banding birds and writing about their habits. Later, it was his curiosity about how animals behave when they live too close together that would make him famous.

Beginning in the 1940s he conducted numerous studies on colonies of rats and mice with the intent of understanding the impact of population on natural harmonious living, self-organization, stress, and changes in behavior.

In 1968, on the Maryland property of the National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], Calhoun created his most famous experiment with mice, Universe 25. It was a mouse utopia that ultimately led to the self-inflicted extinction of the population after 600 days.

In the years after World War II, while his peers were promoting the idea of world overpopulation, e.g. The Population Bomb by Paul Ehrlich, John Calhoun was worried about something different. The problem was not the potential lack of food and resources, as the neo-Malthusians argued, but rather the lack of space.

Before we look at how this experiment unfolded, let’s remember that scientists do not study mice and rats to learn about rodents. No, it is to learn about humans.

Whether we like the idea or not, there are uncomfortable parallels.

Universe 25 was a luxury apartment complex for mice, a utopia with all their needs provided. It was an eight-foot-tall metal tank with 256 nesting boxes, unlimited food and clean water, temperature controlled at 68°F, and an absence of any predators. The structure was cleaned routinely. There were corridors, stairwells, and tunnels. The structure was built to house up to 4000 mice comfortably.

Day one, Calhoun introduced four breeding pairs of mice. They were disease-free, genetically superior specimens from the NIH.

For the first 100 days the mice explored their world, adjusted, and began to reproduce. The next 250 days saw a doubling of the population every 55-60 days, and by day 315 the Universe 25 population was 620.

The 300-day mark represented a turning point in the experiment.

Reproduction dropped dramatically afterward, with the population doubling only every 145 days. The last surviving birth was on day 600, bringing the total population to 2200 mice in a habitat that was built to hold over 3800. But the community’s demise was already certain.

It wasn’t only reproduction that suffered. The behavior of the mice changed toward others and themselves.

What was the problem? There was food and water, safety, and comfort. Yet the increased crowding destroyed everything.

They needed individual space to prosper. Mice had to rub shoulders with others in the stairwells to get to food, water, and sleep quarters – and this proved to be the problem.

Here are some of the findings:

There were more mice than meaningful social roles.

It became impossible to define and defend territory.

Community breakdown led to inability to form social bonds.

There were escalating violent attacks including cannibalism.

Nursing females attacked their own young when left unprotected.

Infant abandonment and mortality increased dramatically.

Calhoun used the term behavioral sink to define this societal collapse and abnormal behavior in the overcrowded population. It seems the mice could not deal with the repeated contact of so many individuals and lost the ability to form normal social bonds.

A specific group of mice were called the beautiful ones. These were healthy mice who withdrew from all social interaction and became passive hermits. They spent their days eating, grooming, and sleeping but avoided sex and fighting. While capable of reproduction, they chose not to or forgot how to mate and raise young, leading to the physical and social death of the habitat.

Calhoun identified two deaths. First is the loss of the capacity for meaningful behavior, the dissolution of social organization, spiritual death. In Universe 25, the mice ceased to be mice before they died. Second is physical death.

In 1962, Calhoun published a paper in Scientific American called Population Density and Social Pathology, laying out his conclusion:

Overpopulation meant social collapse followed by extinction. Once the number of individuals capable of filling roles greatly exceeds the number of roles, only violence and disruption of social organization can follow.

John Calhoun's experiments reveal something important about the nature of crowding and social interaction. It wasn't just about physical space – it was about social space.

When every interaction becomes stressful, when you can't find meaningful roles to play in society, when you are constantly surrounded by others but cannot form genuine connections, then problems arise.

While others used Calhoun’s research to argue about population control or to warn about the dangers of urban life, Calhoun himself had a different message. He believed that creativity and good design could solve these problems.

In his later work, Calhoun found that some mice could thrive in high-density environments. These were the mice that were better at handling lots of social interactions, what he called high social velocity mice. Some of the stressed mice even became more creative and innovative, finding new ways to survive.

We human beings are a higher life form. I do not say otherwise. However, a careful look at some of our urban areas seem to run parallel on some tracks to Universe 25.

Good design matters. The way we structure our living spaces, our cities, and our communities can either support healthy social interaction or undermine it. Calhoun's mice weren't doomed by their numbers – they were doomed by an environment that made healthy social relationships impossible.

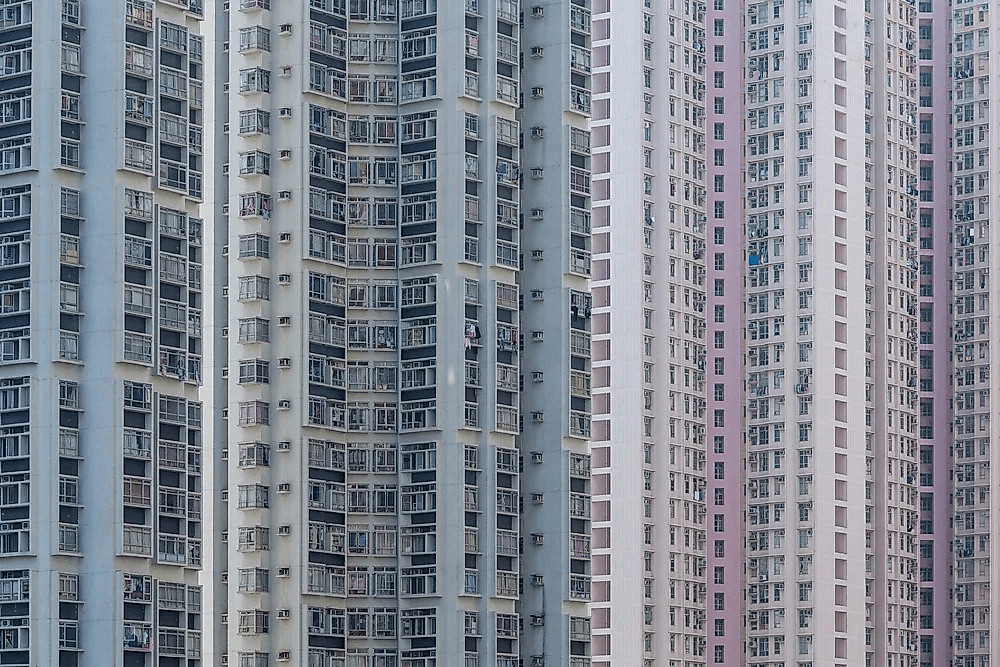

Look at some of the apartment buildings around the world, especially in India and China, the largest population centers. It boggles the mind.

We may be more adaptable than we think. Some mice thrived even in the collapsed society of Universe 25. With our greater cognitive abilities and capacity for creativity, we have even more potential to adapt and find solutions.

Yet, I say we must exercise caution. I don’t believe that we can flourish in such dense living quarters.

What do you think? Can we design better ways of living together where we can create a sense of purpose and connection in an increasingly crowded world?

References

Universe 25- John Calhoun's NIMH experiment

Being Too Connected Hurts Us - Behavioral Sink Experiments and John B. Calhoun

(75) That Time a Guy Tried to Build a Utopia for Mice and it all Went to Hell - YouTube

The Universe 25 Experiment [All Mice Died]

Over 30,000 people live in this building in Hangzou , China

Inside China's MOST Populous Building

Why Chinese President Xi’s $93B Personal Megacity Remains Empty

Hi, I'm Ellen...

... and I am a writer, coach, and adventurer. I believe that life is the grand odyssey that we make of it.

I would like to help you live a truly magnificent and happy life no matter your age and current situation.

You deserve to experience your hero’s journey to its fullest.

What are you waiting for?

There is only now and the next choice.

Subscribe to my email list here

your privacy is protected and you can unsubscribe any time

Subscribe to the Triumph and Grace newsletter

your privacy is protected - unsubscribe any time